Posts By katenelson1

Challenge A: Comic – Curious Milo: Teaching Kids That All Emotions Are Natural

Curious Milo (Educational Comic Project)

Helping Children Recognize and Accept Their Feelings

Updated: September 20th, 2025

Authors: Kate Nelson

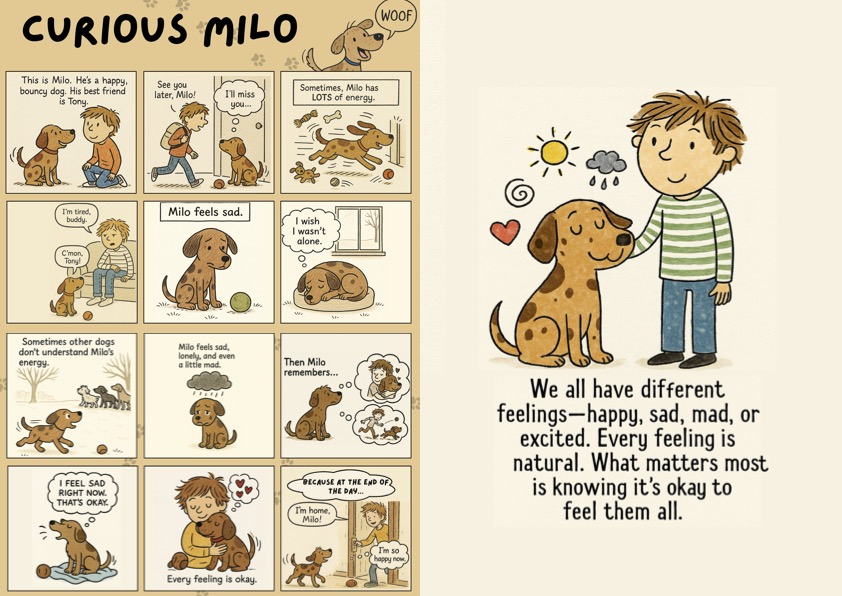

This comic project is Curious Milo, a 13-panel educational comic designed to help children on the autism spectrum recognize and normalize their emotions. The comic follows Milo, a playful and relatable dog, as he experiences a range of feelings — from excitement and joy to sadness and disappointment — and models how all emotions are natural and okay. Structured across clear, sequential panels, the story uses simple narration, speech bubbles, and thought bubbles to make emotional awareness accessible, engaging, and child-friendly.

Understand

CHALLENGE:

Children on the autism spectrum often struggle to recognize, communicate, or express their own emotions, even though they may show empathy when others display feelings. This project uses a relatable dog character to help children understand that all emotions are natural and okay, making emotional awareness more approachable and engaging.

CONTEXT AND AUDIENCE:

Audience (Typical and Extreme Cases):

This project is designed for children on the autism spectrum, primarily between the ages of 6 and 10. Some may simply need extra support recognizing and labeling feelings, while others may depend heavily on visuals or non-verbal methods.

Needs:

In my work with children on the spectrum, I’ve noticed they often find it easier to empathize with a character, animal, or someone else showing feelings than to recognize those same emotions in themselves. They need clear, safe, and playful ways to externalize emotions. Milo, a bouncy and relatable dog, provides that lens by modeling a range of feelings.

Goals:

The goal is to help children see emotions as natural and temporary. For some, that means naming or pointing to a feeling, while for others it might simply be feeling safe enough to acknowledge them.

Motivations and Factors:

Demographically, the audience is young school-aged children supported by teachers, caregivers, and families. Psychographically and behaviourally, they respond best to clear visuals, predictable stories, and relatable characters rather than abstract explanations. This project aligns with those needs by keeping the story simple, structured, and engaging.

POV STATEMENT:

A child on the autism spectrum needs a safe and relatable way to see emotions modeled clearly so that they can begin to recognize, accept, and express their own feelings.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

Main objective:

Children on the autism spectrum will be able to recognize their feelings in a healthy way by learning that all emotions are natural and okay.

Sub-Objectives:

- Identify at least four core emotions (happy, sad, lonely, mad).

- Relate personal experiences to Milo’s story (e.g., “I feel like Milo when…”)

- Practice expressing emotions through words or non-verbal strategies.

- Understand that feelings come and go, and it is safe to feel them all.

- Build empathy by recognizing that others (like Milo or Tony) also have feelings.

Secret Learning Objective:

Encourage meta-cognitive awareness by helping children reflect on how emotions affect their behaviour, and foster empathy towards themselves and others.

Plan:

IDEATION:

When I started brainstorming, I first imagined a comic about a child going through everyday situations and experiencing different emotions. As I reflected more, I thought about the children with autism that I work with and how they often find comfort in animals and characters rather than human figures. This led me to shift my idea and create Curious Milo, where a relatable dog models a variety of feelings across simple, sequential panels that combine visuals with short text.

STORYBOARD OR SCRIPT:

The comic follows a 13-panel sequence:

- Milo wagging next to Tony – introduction.

- Tony leaves; Milo thinks, “I’ll miss you…”

- Milo bursts with energy.

- Tony is tired; Milo wants to play.

- Milo feels sad with his ball.

- Milo curled up by the window.

- Dogs turn away at the park.

- Milo with a storm cloud overhead.

- Milo remembers happy moments (memory bubbles).

- Milo howls softly, then cuddles his blanket.

- Tony returns home.

- Tony hugs Milo – “Every feeling is okay.”

- Reflection panel showing that all emotions are natural and safe.

Each slide includes narration, speech bubbles, or thought bubbles to model both external and internal experiences of emotion.

PRINCIPLES APPLIED:

I applied Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML) and multimedia principles:

- Coherence: Each panel focuses on one clear idea or feeling.

- Contiguity: Speech and thought bubbles are placed close to the character.

- Segmenting: The story is broken into short, digestible slides.

- Dual Coding: Text is paired with Milo’s visuals to reinforce meaning.

- Personalization: Text is conversational, using simple, direct language.

- Signaling: Emotion is reinforced with symbols (hearts, storm clouds, sunshine).

Create and Share the Prototype

The final artifact is a 13-panel educational comic titled Curious Milo. It was created using ai-generated, child-friendly visuals in a sketchy style (similar to Charlie and Lola), combined with narration, speech bubbles, and thought bubbles. The sequence models common feelings children may experience and reinforces that every emotion is okay.

While I did use ChatGPT to help generate the base images, I used apps such as Canva and Google Docs to edit the images and style it in the way that represents my personal creativity. Prompts were made to detail and input the script of each comic section, as well as the top newspaper-style framing with the title and peek of Milo in the corner.

PEER FEEDBACK:

I was unable to participate in the peer feedback stage, but I engaged in self-reflection and iterative corrections. This included fixing inconsistencies in text (ensuring correct grammar like “I’ll miss you”), standardizing Milo’s look, and addressing visual continuity. I also that AI-generated images can sometimes produce flaws (extra features, slight colour shifts), and I corrected or regenerated those panels to ensure accuracy.

Reflect and Refine

TEAM REFLECTION:

Since I worked individually, my reflection centers on my own design process. What worked well was the comic’s ability to clearly communicate feelings through Milo’s expressions and thought bubbles. Using a dog character was effective because children often find animals safe and relatable.

If I were to improve the project, I would test it directly with children to see how they respond to Milo and whether the story helps them articulate feelings. I would also add interactive elements, such as prompts asking children to point to the emotion Milo is feeling, or spaces for them to draw their own “feeling bubbles.”

A limitation of this type of multimedia is that while comics are engaging, they are static. They can show feelings clearly, but they don’t allow for dynamic practice the way games or role-plays might. Still, comics are powerful because they combine storytelling with visuals and text in a way that supports children who benefit from structure and predictability.

INDIVIDUAL REFLECTIONS:

As the sole designer, I carried out all stages of the project, from ideation to artifact creation. I learned the importance of consistency when working with AI-generated images, as small details can drift between panels. More importantly, I deepened my understanding of how multimedia learning principles apply to practice: by keeping design simple and structured, I could make an abstract topic like emotions accessible for children.

References:

https://edtechuvic.ca/edci337/2025/09/05/theories-of-multimedia-learning/

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. Images generated using DALL·E. https://chat.openai.com/

Blog Post #1: Personalized Learning in My Own Words

What Personalized Learning Means to Me

When I think about personalized learning, I see it as a balance between structure and choice. It’s not about throwing out standards or goals—it’s about creating space for students to connect learning to their own lives, interests, and needs. That’s what makes learning stick.

How I’ve Experienced It

One clear example for me comes from a sociology course I took last year. For my final paper, I was able to use my own experiences within a capitalist system and connect them with current articles in academia to build a research essay that felt both rigorous and authentic. The assignment framework was the same for everyone, but the freedom to personalize the topic gave me a sense of ownership over the work. Instead of just checking a box, I was building something meaningful.

This is what personalized learning feels like in practice: the mix of guidance and choice that pushes me to engage more deeply.

Where PLNs Fit In

In our readings for EDCI 338, Green (2016) describes Personal Learning Networks (PLNs) as formal and informal networks where people with similar goals collaborate, share resources, and learn together. I like to think of PLNs as webs of connections—threads linking me to people, tools, and ideas that expand my learning beyond a single classroom. For example, I follow teachers on Instagram who share literacy strategies and playful math activities. Those posts become part of my web, giving me practical insights that I can filter and personalize to fit my own goals. What makes it powerful is that I get to choose which strands of the web matter most to me, building a PLN that feels both flexible and personal.

Of course, there are challenges too. Social media can easily slide from purposeful learning into distraction. I’ve noticed that when I use it with intention—searching for strategies or perspectives—it becomes a valuable part of my PLN. When I scroll passively, it doesn’t add much. That intentionality feels like another layer of personalized learning: knowing my goals and choosing resources that support them.

Why It Matters

What I take away from these experiences is that personalized learning isn’t just a K–12 idea—it’s shaped my university experience and will continue to shape how I learn and teach. Having choice and ownership in my sociology paper made me more invested in the outcome. Building PLNs through social media lets me expand my learning beyond the classroom.

As I prepare to become an educator, I want to carry these lessons forward. I want students to feel the same sense of ownership I’ve felt—because learning feels most powerful when it connects to who we are and what we care about.

References

Green, C. (2020) “Chapter 5: Personal Learning Networks: Defining and Building a PLN” in Learning in the Digital Age by Tutaleni I. Asino. Oklahoma State University. https://open.library.okstate.edu/learninginthedigitalage/chapter/personal-learning-networks_defining-and-building-a-pln/

Assignment #3: Community Contributions

Blog #1:

Hi Ella,

I really enjoyed reading your post! I also appreciate the constructivist approach to teaching and agree that hands-on, real-world applications help students absorb information more effectively. The sensory activity you described for teaching the senses sounds like a fantastic way to engage students in a memorable and meaningful way. It’s clear that you’re focused on creating learning experiences that connect with students’ everyday lives, which is so important for making concepts stick.

Since you mentioned how much you remember from similar activities in your own childhood, I’m curious—how would you adapt this type of hands-on activity for a virtual or hybrid classroom setting, where students might not have easy access to physical materials? Could there be a way to replicate this kind of sensory experience using digital tools or virtual activities?

I really admire how you’re shaping your teaching philosophy, and I’m excited to see how your constructivist approach will come to life in the classroom. Keep up the great work!

Blog #2:

Hi Cassie!

I really enjoyed reading your post on the comparison between direct instruction and open pedagogy in programming. You’ve made a clear and well-structured argument for how both approaches can complement each other depending on the learner’s stage. I love how you highlighted the value of direct instruction for beginners to build a solid foundation and how open pedagogy encourages creativity and critical thinking in more advanced learners. It’s a balanced approach that seems effective for a wide range of learners.

Since my approach focuses on experiential learning, I’m curious about how you might integrate more hands-on, real-world activities into the open pedagogy approach for programming. For example, could students work on coding projects that address specific, real-world problems, allowing them to apply both the foundational knowledge and the creative problem-solving skills they’ve developed through exploration?

I’d love to hear more about how you might blend elements of experiential learning into the open pedagogy framework!

Blog #3:

Hi Omid!

I really like how you’ve designed the learning resource with such a variety of activities to cater to different learning styles—visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. The flexibility you’ve built into your approach is fantastic, especially the inclusion of differentiated activities that let students work at their own pace. It’s great that students can engage in ways that suit their strengths, whether they’re sketching in nature journals or collaborating in group discussions.

Your plan for adapting the resource in case of unexpected events, like a pandemic, is also impressive. Transitioning to remote learning can be challenging, but I love how you’ve maintained the essence of the outdoor exploration experience by having students observe trees in their surroundings and share their findings online. I’m curious, for the nature journal, would you incorporate any collaborative elements in the digital format? For instance, could students share their sketches and observations with classmates for feedback or discussion?

Looking forward to hearing more about how you might expand on these ideas!

Blog #4:

Hi Ella!

I really love your idea of having students create a short video to explain what they learned from the video—especially since we’re working on this project together, I can see how this approach would be a great way for students to synthesize and present information creatively. I love the flexibility you’ve provided with the different video formats (like music videos or news anchor styles), which will allow students to express their understanding in their own unique ways.

Since we’re both focusing on the balance between creativity and meeting learning objectives, I’m curious about how you might assess those videos, especially if a group leans more towards a creative or abstract approach. Would you adjust your feedback criteria to ensure the key points are still covered, or might you consider a rubric that balances creativity with content?

Also, I really appreciate how you’ve thought about inclusivity, especially for students who might feel uncomfortable being on camera. The voice-over option is a great solution. Do you think adding a brief reflection on the video-making process might help students engage more deeply with their learning, particularly for those who might not be as comfortable with video production?

Looking forward to hearing more of your thoughts on this, especially as we continue to develop our project together!

Hi Bashar,

I really liked the way you designed your interactive activity around Alzheimer’s Disease, especially how you combined the video content with note-taking and follow-up questions. It’s great how you’ve structured it to build knowledge progressively, from video viewing to assessments like Kahoot. This approach seems appropriate for reinforcing the learning and ensuring students have a solid understanding of the topic.

Since the video serves as a stepping stone to further activities, I’m curious—how would you ensure that students who might find the topic of Alzheimer’s particularly sensitive or emotional are supported during the activity? Could you include additional resources or support for these students to navigate the content more comfortably?

Overall, I think this is a great, manageable activity for learners, and it seems like it could easily be scaled to fit various group sizes. Looking forward to hearing your thoughts!

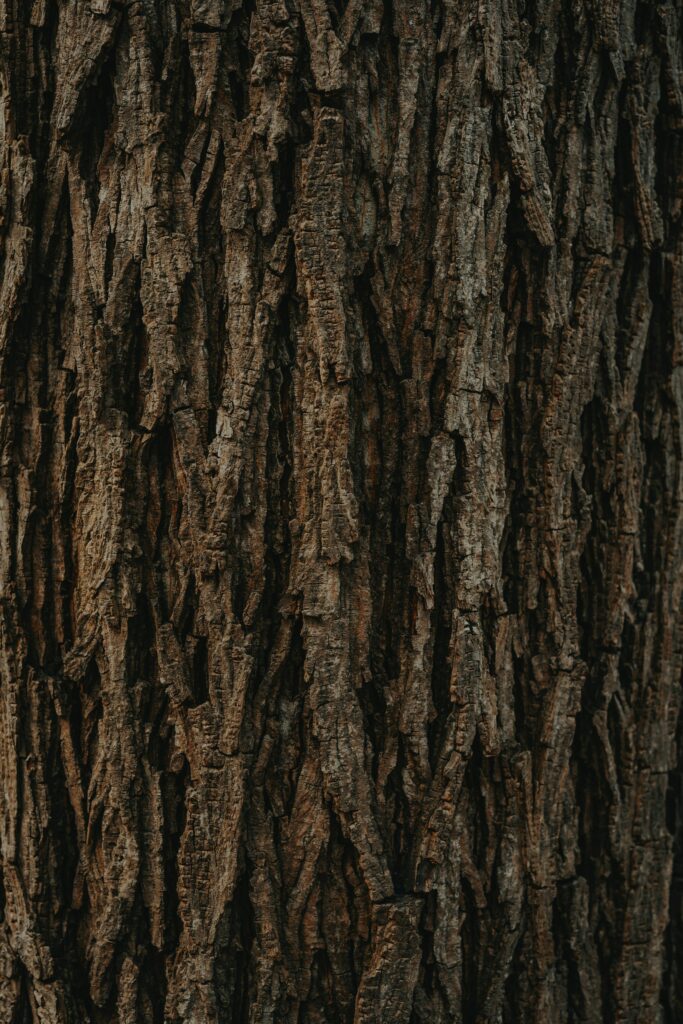

Blog Post 4: Interaction

For our ongoing project on tree identification in British Columbia, I discovered a YouTube video called “Identify 11 Trees by the Bark (Easy Tips)”. While some of the featured species aren’t strictly representative of BC’s forests, the bark-identification techniques still serve as valuable examples. Students can cross-reference these tips with a local guide or an alternative video focusing on BC trees, then mentally match those traits to species in their own neighbourhoods.

1) Type of Interaction

This video primarily fosters learner-content interaction. Students observe close-up shots of bark—examining color, texture, and vertical grooves—and then compare what they see to what they might encounter in local areas. Although there’s no embedded quiz, the inherent curiosity factor prompts them to think critically about each species’ traits.

2) Learner-Generated Response

Students would likely take notes during the video—jotting down whether the bark is smooth or peeling, noting color variations, etc. This self-directed approach encourages them to create personalized study aids, tying into the principle that active, meaningful engagement leads to deeper understanding.

3) Post-Viewing Activity

To connect the video’s content to BC trees, I’d suggest a “Bark Scavenger Hunt.” Students photograph or sketch bark from local trees and upload their findings to a shared platform (e.g., Padlet). They can note which features align with tips from the video, or reference an alternative, BC-specific tree list. This blend of learner-learner and learner-contentinteraction helps them refine identification skills while learning from peers.

4) Feedback Mechanism

In the shared digital space, peers and I could provide feedback—suggesting whether a certain bark feature matches a Douglas-fir or a Western redcedar, for instance. This collaborative process can prompt further investigation and reinforce observational skills. Encouraging students to question and respond to each other’s findings helps keep the conversation active, while guiding them to refine their identification approaches through peer support and instructor insights.

5) Addressing Potential Barriers

Students without nearby green spaces can find bark images online, allowing everyone to participate. Additionally, providing closed captions or transcripts ensures that those with hearing impairments or limited bandwidth can still benefit from the video. By offering multiple ways to engage, we strive to keep the activity inclusive and accessible to all learners.

Through a combination of video content, hands-on exploration (whether physical or virtual), and collaborative feedback, students can sharpen their identification skills while gaining a deeper appreciation for the variety of trees in BC—and beyond.

References:

Interactive Learning Resource

Ella Meldrum, Kate Nelson, Omid Izadi

EDCI 335 Spring 2025

OVERVIEW

British Columbia is home to a diverse range of native tree species, shaped by the province’s varied climates and ecosystems. Accurately identifying these trees is crucial for forest management, conservation efforts, and ecological research. Tree identification relies on several key characteristics, including leaf morphology, bark texture, reproductive structures, and habitat preferences. Some of the most common native trees in BC include Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), Western redcedar (Thuja plicata), Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), and Garry oak (Quercus garryana). Douglas-fir is distinguished by its thick, furrowed bark and pointed buds, making it one of the most widespread conifers in the province. Western redcedar, known for its reddish-brown, peeling bark and scale-like leaves, dominates coastal rainforests and holds cultural significance for Indigenous communities. Sitka spruce thrives in moist coastal environments and is identifiable by its sharp, stiff needles and thin, scaly bark. Garry oak, BC’s only native oak species, features lobed leaves and rough, ridged bark, mainly found in the province’s southern regions.

- Government of British Columbia. (n.d.). Tree species compendium. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/forestry/managing-our-forest-resources/silviculture/tree-species-selection/tree-species-compendium-index

- Great Bear Rainforest Trust. (n.d.). Tree book: Learning to recognize trees of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://dev.greatbearrainforesttrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Treebook.pdf

CONTEXT:

The learning context focuses on elementary school students. These students are in the early stages of developing an understanding of their natural environment and are naturally curious about the world around them, and it is important to help them develop meaningful connections with the surrounding environment.

Educational Background & Prior Knowledge

- Students may have basic exposure to trees and nature through outdoor activities, schoolyard observations, or family outings.

- They may recognize common trees but might not yet understand species differences, ecological roles, or conservation importance.

- The course is done in British Columbia so it is safe to assume that all the students can have access to parks and natural spaces.

Interests & Lifestyle

- Many children in this age group enjoy hands-on learning, outdoor exploration, and interactive activities.

- They engage well with visual and tactile learning methods, such as nature walks, tree sketching, and group discussions.

- Digital tools, such as interactive worksheets and online platforms, can enhance their engagement.

Specific Learning Needs

- Providing simplified terminology and structured guidance helps younger learners grasp complex ecological concepts.

- To accommodate colorblindness when identifying tree colors, rely on features such as leaf shape and bark texture, avoid red-green pairings, use colorblind-accessible palettes with added symbols or patterns, and include clear descriptive language.

LEARNING THEORY

Constructivism:

The constructivist learning theory emphasizes that learners build knowledge through active exploration, experience, and social interaction rather than passive memorization. In this approach, students construct their own understanding by engaging with real-world concepts, asking questions, and drawing connections to prior knowledge. Learning is most effective when students interact with their environment, engage in hands-on activities, and collaborate with peers. Constructivism encourages critical thinking and inquiry, making it particularly useful for subjects that involve observation, classification, and pattern recognition, such as tree identification.

Rationale:

This theory is well-suited for teaching tree identification in BC because it allows students to engage directly with their surroundings, reinforcing learning through observation, discussion, and practical application. Instead of simply reading about trees, students participate in nature walks, sketching, and interactive identification exercises, making the learning process experiential and meaningful. By constructing their own understanding, students are more likely to retain information, develop problem-solving skills, and foster a connection with the natural environment. This approach also encourages environmental awareness and conservation, as students learn not just to recognize trees but to appreciate their ecological significance.

LEARNING DESIGN

The inquiry-based learning design encourages students to explore, ask questions, and actively seek answers through observation and investigation. Instead of passively receiving information, learners take an active role in constructing knowledge by engaging in hands-on activities, such as nature walks, tree identification exercises, and collaborative discussions. This design aligns with the principles of constructivism, allowing students to build understanding through real-world experiences and guided discovery. Inquiry learning promotes critical thinking, problem-solving, and curiosity, making it an ideal approach for topics that involve classification, observation, and environmental awareness.

This learning design is particularly effective for teaching tree identification in BC because it immerses students in their natural environment, making the learning process engaging and meaningful. By exploring local trees, students observe differences firsthand, test hypotheses, and refine their understanding through trial and discussion. Inquiry-based activities, such as identification games, nature journaling, and peer discussions, help learners develop pattern recognition skills and connect knowledge to their daily lives. Additionally, this approach fosters a sense of environmental stewardship, encouraging students to appreciate and protect their surroundings. By allowing learners to actively participate in their own discovery process, inquiry-based learning makes tree identification both interactive and impactful.

INCLUSION

To ensure all students can engage meaningfully with the tree identification resource, we apply Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles from CAST. These principles, Multiple Means of Engagement, Representation, and Action & Expression ensure accessibility, flexibility, and inclusivity.

Engagement: Making Learning Relevant and Motivating

Students will have choices in how they interact with the content, such as through nature walks, interactive slideshows, or video-based learning. Activities will connect to real-world experiences, including Indigenous perspectives on BC’s native trees. Group discussions and peer collaboration will support social learning, while scaffolding and optional challenge levels will allow for differentiated support.

Representation: Providing Information in Multiple Ways

To accommodate diverse learning styles, tree identification materials will be available in various formats. Visual supports include infographics, comparison charts, and labeled images, while auditory learners will benefit from videos with captions and audio recordings. Tactile learners can engage through hands-on exploration, such as collecting leaves and touching bark. Language supports, including bilingual resources and Indigenous terminology, will make learning more inclusive for all students.

Action & Expression: Offering Flexible Ways to Demonstrate Learning

Students will have multiple ways to show their understanding. They can create digital or physical nature journals, present findings through slideshows or videos, or complete interactive worksheets. Assistive technology, such as speech-to-text tools and alternative input methods, will support students with writing or motor challenges. Group projects and peer feedback will further encourage engagement and diverse perspectives.

By incorporating UDL and CAST principles, this learning resource ensures that all students, regardless of ability, background, or learning style, can develop ecological literacy in a way that works best for them.

A rationale for your technology choices.

The technology selected enhances interactive, inquiry-based learning, making tree identification engaging and accessible for elementary students.

- Padlet facilitates peer collaboration by allowing students to upload tree photos and descriptions, promoting discussion and shared learning.

- TreeBee provides an interactive tree identification tool, aligning with inquiry-based exploration.

- YouTube videos, infographics, and slideshows support visual and auditory learners, making ecological concepts easier to understand.

- QR codes and discussion forums encourage students to share and compare findings on tree importance.

- Nature walks with digital journaling integrate hands-on learning, reinforcing constructivist principles.

- Speech-to-text tools and digital platforms (Google Classroom/Moodle) ensure accessibility and flexibility, allowing students to learn at their own pace.

These tools create a dynamic, inclusive, and engaging learning experience, ensuring students actively explore, collaborate, and apply their knowledge.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this course:

Module 1:

Students will be able to recognize and name different BC native trees.

Module 2:

Students will be able to identify different types of trees based on their physical attributes.

Module 3:

Students will be able to understand the ecological importance of BC native trees.

COURSE OUTLINE:

MODULE 1: BC Native Trees

Let’s embark on an exciting journey into the world of British Columbia’s native trees! This module introduces you to the rich diversity of coniferous and deciduous trees that flourish in our local ecosystems. You will learn to identify these trees, explore how they adapt to various environments, and delve into understanding their crucial roles in nature. Through engaging and accessible activities, every student will have the opportunity to connect with and appreciate the natural beauty and ecological importance of these trees.

Coniferous Trees:

- Characteristics: These are strong trees that keep their green needles all year round and grow cones for reproduction. They are also known as evergreens or softwoods.

- All image sources: Various iNaturalist Research-Grade naturalists.

- Key species:

- Douglas-Fir: These trees come in two forms; the coastal and the interior, which vary in height and habitat. These provincial classics are characterized by their flat, pointy yellow needles, cones with bracts, and thick dark grooves. You can also tell them apart from the rest based on its overall shape, which is triangular, pointing towards the top with a long bare trunk.

- Sceintifc name: Pseudotsuga menziesii. SENĆOŦEN (W̱SÁNEĆ) name: JSȺ¸IȽĆ.

- Sitka Spruce: These trees are the humongous type! While these coastal greats can be recognized for their scaly, flaky greyish bark, they also have features such as sharp slightly flattened needles with four sides and yellowy-brown seed cones.

- Scientific name: Picea sitchensis. HlGaagilda Skidegate (Haida) name: Kayd.

- Western Red Cedar: These trees are mighty beasts! The tree of British Columbia, this tree has a very tall trunk with large hanging branches. They are typically easy to recognize, but you can find them with details such as their scale-like leaves, grey stringy bark, and egg-shaped cones.

- Scientific name: Thuja plicata. SENĆOŦEN (W̱SÁNEĆ) name: XPȺ¸.

- Douglas-Fir: These trees come in two forms; the coastal and the interior, which vary in height and habitat. These provincial classics are characterized by their flat, pointy yellow needles, cones with bracts, and thick dark grooves. You can also tell them apart from the rest based on its overall shape, which is triangular, pointing towards the top with a long bare trunk.

- Learning Highlight: You’ll explore how these trees withstand the changing seasons and why they are important to both our environment and our communities.

Deciduous Trees:

- Characteristics: These trees celebrate the seasons by changing colours and shedding their leaves each fall. They reproduce by growing flowers that turn into fruits or nuts. They are also known as broadleaf trees or hardwoods.

- All image sources: Various iNaturalist Research-Grade naturalists.

- Key Species:

- Bigleaf Maple: This mighty tree is something special, the tallest species of Maples in Canada! These trees tend to grow differently according to their habitat, but in forests they are quite narrow at the top. Their leaves are among the biggest in Canada, which earned it its name, some of the leaves being as wide as a ruler! To recognize the tree for its leaves, you can see a dark green and shiny top, and when the seasons change they turn yellow. This tree produces small greenish-yellow flowers in the spring and winged seeds in the fall.

- Scientific name: Acer macrophyllum. SENĆOŦEN (W̱SÁNEĆ) name: ȾŦÁ,EȽĆ.

- Black Cottonwood: These trees are quite unique! While they are strong, large, and straight, they also have massive buds that are sticky (also called catkins)! You can recognize these trees by their dark green and shiny leaves, their big catkins, and the released seeds that are white and fluffy!

- Scientific name: Populus balsamifera spp trichocarpa. SENĆOŦEN (W̱SÁNEĆ) name: ĆEU¸NEȽP.

- Bitter Cherry: This tree is on the smaller side! While they appear more like shrubs, these trees can be recognized by their oval-shaped leaves, small white flowers and dark red bitter fruit. While you probably wouldn’t enjoy the fruit from this tree, there are a number of uses of the bark, such as the way the Indigenous people made waterproof baskets and mats.

- Scientific name: Prunus emarginata. Hul’q’umi’num’ name: t’ulum’ulhp.

- Bigleaf Maple: This mighty tree is something special, the tallest species of Maples in Canada! These trees tend to grow differently according to their habitat, but in forests they are quite narrow at the top. Their leaves are among the biggest in Canada, which earned it its name, some of the leaves being as wide as a ruler! To recognize the tree for its leaves, you can see a dark green and shiny top, and when the seasons change they turn yellow. This tree produces small greenish-yellow flowers in the spring and winged seeds in the fall.

- Learning Highlight: You’ll investigate how these trees support wildlife and what happens in their life cycle throughout the year.

LEARNING ACTIVITY IDEA:

Tree Exploration Walk: Embark on a nature walk around your school or a nearby park or forest, wearing your explorer hats! During this walk, you’ll have the opportunity to observe a variety of trees, gather interesting facts, and experience firsthand the subjects we’re studying in class. This activity is designed to bridge classroom learning with the tangible, natural world around us.

Alternative Virtual Exploration: For students with mobility limitations or who cannot join the physical walk, we will provide virtual tours of BC forests using Google Earth and interactive videos. These tools offer a dynamic way to explore different environments and learn about tree species without physical travel.

MAIN ACTIVITY:

Tree Profile Journal

- Objective: You will create a Tree Profile Journal that will serve as your personal guide to the trees we study. This booklet will include your own observations, drawings or photos, and various facts about each tree, helping you to document and reflect on your learning experience.

- Components: Each tree will have its own page featuring visual and textual information, including the tree’s common and scientific names, key characteristics like whether it produces cones, fruits, or nuts, its bark texture, its leaf or needle description, and a personal observation or interesting fact.

- Instructions:

- Research and Observation: Collect information through our guided walks, virtual tours, and available digital and print resources.

- Booklet Creation: Use the provided template to assemble your Tree Profile Journal. This template is designed to be informative and visually appealing, facilitating an organized way to compile your findings.

- Personal Insight:Write a section on why you think each tree is important or interesting, helping you to connect personally with the material.

- Alternative Reflection Methods: We recognize that some students may find traditional writing challenging. Therefore, you are encouraged to submit video or audio reflections through a course Learning Management System (LMS) if this better suits your learning style. These reflections can discuss what you find significant or fascinating about each tree, allowing for personal expression in various formats.

Edited OER Resource: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1XcjdqTznjlS4Q6kCOvoh6BGw6QzMxPso/view

https://natureinspiredlearning.com

Tree Book – learning to recognize trees of British Columbia

https://portal.fpbc.ca/Files/students/Gr4-5wonderfulworkingsofwood.pdf

Native Plant Names – SENĆOŦEN & English

Future of Technology in Education: Benefits and Trends

The Trees of Haida Gwaii: Haida Tourism

MODULE 2: Identifying Trees Physical Attributes

Deciduous Trees:

Leaves:

Simple: just one leaf, undivided

Compound: the leaf is composed of many leaflets

Image: https://www.ourcityforest.org/blog/2020/4/22/tree-identification-tips

- Pinnately Compound: The leaf is made up of many leaflets and they are arranged on both sides of a central stalk

- Palmately Compound: The leaf is made up of many leaflets and they come from one point. Think of it like your fingers coming out from the palm of your hand

Image: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/leaf-structure-characteristics/

Arrangements of leaf buds:

Opposite: the leaves or branches are attached directly across from each other

Alternate: The leaves or branches are attached singly and alternate

Image: https://www.uwgb.edu/biodiversity-old/herbarium/trees/alternate_opposite_leaves01.htm

SMOOTH ROUGH

Edges of the leaves:

Smooth: the leaf edges are smooth or the lobes of the leaf are wavy

Rough: The leaf edges are toothed or the lobes of the leaf are pointy.

Image: http://www.irwantoshut.com/tree_leaf.html

Broad Narrow

Blade Shape:

Broad: Leaves wider at the base then the tip.

Narrow: Leaves longer than they are wide.

Coniferous Trees:

Images: https://treebee.ca/identify-a-tree/

Needles: The needles are attached to the step, either in bundles or singly.

- How many needles are in a bundle?

- What is the length of the needles?

Image: https://reliabletreecare.com/tree-services-cleaning-up-pine-needles/

Scales: The leaves are overlapping scales

Images: https://treebee.ca/identify-a-tree/

ACTIVITY:

Tree Identification

Instructions:

- After learning the different characteristics used for classification

- Go into your backyard, find a tree and answer the questions on the website that matches the physical characteristics to identify what tree it could be.

- If you are unable to find a physical tree within nature choose an image from the internet of a tree and use its physical characteristics to complete the activity.

- Follow the link to the website, where you will answer a series of questions based on the characteristics of the tree you have chosen.

- You have the option for this activity to work alone or with a partner, the choice is yours to make! ( if you are working in pairs make sure both names are attached on the discussion post).

https://treebee.ca/identify-a-tree/

ACTIVITY DISCUSSION:

Instructions:

- After you identify the tree that you find using its physical characteristics add the picture you took and the description of what tree it is to the discussion forum on padlet!

- See what characteristics other people found and what trees they identified!

- Bonus: Research and add where that specific tree is found!

https://padlet.com/ellameldrum99/post-your-pictures-and-descriptions-that-you-found-w0tc8x50tlg7hkh1

MODULE 3: The Ecological Importance of Trees

I’m sure we have all heard that trees are important to us as human beings and our environment, but why are they important? In this module you will learn through multiple resources the ecological importance of trees, you will be able to then explore the importance of trees within your own research! After viewing the material I have provided for you, you will find your own resources that you find, then you can explore the resources that your peers have found!

VIDEO:

Watch this video to learn more about why trees are important through specifically learning about the 6 key pillars of how trees help us and our environment.

READING:

Read the following article to understand the importance of trees:

https://www.savatree.com/resource-center/tree-varieties/why-trees/

DISCUSSION ACTIVITY:

It is now YOUR turn!

Instructions:

- After engaging in the material I have provided you with throughout this module, you will now use the internet to research and find your own resources that demonstrate the importance of trees.

- Look for articles, images, videos that you think demonstrate the key in why trees are important to us as humans and the environment. Add a comment on why you chose that resource.

- View and explore other resources that your peers find to understand the concept further!

Scan the QR code or press the link and add a discussion post to the forum

https://padlet.com/ellameldrum99/why-do-you-think-trees-are-important-to-ecosystems-89q82luynxce3cdb

ASSESSMENT Plan Overview

Formative Assessments:

Formative Learning Activities:

Each module has a formative assessment that is engaging for the learner.

- Module 1: Tree Profile Booklet – This activity can be printed or submitted online. 20%

- Module 2: Tree Identification Activity/ Discussion – This activity is in the form of a padlet. 20%

- Module 3: Research Discussion Activity – This activity is in the form of a padlet. 20%

Formative Assessment Rationale

Module 1: Tree Profile Booklet

This formative assessment engages students in identifying BC native trees by their physical characteristics, applying their knowledge in a practical, hands-on way. Students will explore their local environments, such as schoolyards and neighborhood parks, to select trees and use the information learned in class to create detailed profiles in their Tree Profile Booklets. The assessment supports various learning styles and needs by offering the booklets in multiple formats, including digital and large-print versions for better accessibility.

To enhance the educational value and cultural sensitivity of the module, Indigenous names and traditional uses of the trees will be integrated into the booklet content. This inclusion not only respects and acknowledges the rich cultural heritage associated with the local flora but also provides students with a more comprehensive understanding of each tree’s significance. Feedback will focus on the students’ ability to incorporate both scientific and Indigenous knowledge effectively, promoting an inclusive and collaborative learning environment.

Module 2: Tree Identification Activity/ Discussion

This formative assessment allows students to discuss their understanding of how to identify trees using their physical attributes in a way that engages them through their physical surroundings and understanding the different characteristics of different trees. Students can choose their own tree within their environmental surroundings and use the information they have learnt about tree characteristics to identify its name. This inquiry-based formative assessment will enable students to engage in their real-life surroundings to demonstrate their knowledge about the material they have learned.

Feedback for this assessment will be provided to learners individually regarding their engagement and participation in the activity and discussion and their interaction with others’ discussions and comments.

Module 3: Research Discussion Activity

This formative assessment allows students to demonstrate their understanding of the importance of trees by researching and sharing the resources they find and engaging with resources other peers find. This allows the instructor to assess the learners’ understanding through their chosen resources and their comments. This inquiry-based formative assessment will enable students to engage in their own research and build their own knowledge through the exploration of resources.

Feedback for the assessment will be provided to the learners individually in regards to their resource selection and more specifically their reasoning for their selection, as well as their engagement with peers’ resources researched.

Summative Assessments:

Tree Ambassador Portfolio (40%)

Overview:

The Tree Ambassador Portfolio challenges students to become ambassadors for a tree they have studied, demonstrating a comprehensive understanding of its characteristics and ecological importance. This portfolio is meticulously structured to be inclusive, accommodating all students by facilitating full participation and expression of their learning, overcoming any potential barriers.

Components:

- Research Compilation: Students compile detailed information about their chosen tree, including its identification, physical attributes, and ecological roles. This component integrates classroom resources with accessible online tools, and incorporates Indigenous names and traditional uses of the trees to respect and acknowledge the Indigenous cultural heritage associated with the local flora.

- Creative Element: Students create a personalized piece related to their tree, which can be an art project, a digital presentation, or a written story. This element is tailored to individual capabilities and resources, ensuring that each student can express their connection to the tree in a way that suits their unique learning style and accessibility needs.

- Conservation Message: The portfolio includes a proactive plan for advocating the tree’s conservation within the community. This might involve activities like planting trees or removing invasive species, detailed in a way that respects both ecological and cultural sensitivities.

- Presentation Options: Students have the flexibility to choose their presentation method—live demonstrations, digital submissions, or detailed written descriptions—accommodating different comfort levels and varying access to technology.

Flexible Completion Options:

- Digital Portfolios: Enables students to use digital tools to assemble and present their portfolios, ideal for those with physical limitations or who prefer a tech-based approach.

- Home-Based Activities: Adjustments to allow observations and activities to be conducted in familiar environments, such as home or nearby parks, ensuring all students have the opportunity to engage with the project.

- Assistive Technologies: Encouragement of technologies like speech-to-text and video recording to assist in the research and compilation phases of the project.

Assessment Rationale:

The Tree Ambassador Portfolio serves as a comprehensive summative assessment that encapsulates all learning outcomes from the course, promoting deep knowledge integration about British Columbia’s native trees. This project assesses students’ understanding across multiple domains: content knowledge, creativity, conservation advocacy, and presentation skills. Each component is essential for students to effectively advocate for their chosen trees and engage in environmental stewardship within their communities.

The assessment criteria are aligned with a proficiency scale—Emerging, Developing, Proficient, and Extending—suitable for elementary students. This scaling facilitates an accurate evaluation of the student’s current understanding and provides a clear pathway for future improvement. By mapping the assessment to these levels, the portfolio accommodates a wide range of abilities, ensuring inclusivity. Key focus areas include the accuracy and depth of content knowledge, the personalization and creativity in expressing a connection to the tree, the practical application of conservation strategies, and the effectiveness of presentation skills, crucial for their roles as ambassadors.

- Content Knowledge focuses on the accuracy and depth of the students’ understanding of tree characteristics and ecological roles, foundational for any subsequent conservation efforts.

- Creativity and Personalization assess how students express their connection to the tree, fostering a personal relationship with nature that is crucial for long-term environmental engagement.

- Conservation Advocacy evaluates students’ ability to apply their knowledge in developing practical strategies for tree conservation, emphasizing the application of learning in real-world contexts.

- Presentation Skills are crucial for effectively communicating their ideas and advocacy plans, a skill essential for their roles as ambassadors.

Grading:

British Columbia’s elementary schools use a proficiency scale instead of letter grades for K-grade 9. Therefore our grading scale will be based off of the proficiency scale using “emerging” “developing” “proficient” “extending” that are clearly outlined and described below:

- Instructors also provide written feedback to the learners.

Peer Review Suggestions From Group I: Melody Hung, Mehr Virk, Simran Gill, and Sashi Siriratne

Module 1: BC Native Trees

- For learners with mobility limitations or accessibility barriers, it might be helpful to have more methods of exploration other than digital images

- Suggestions: Google Earth for a virtual tour of BC forests, or interactive videos

We have added in considerations for mobility or accessibility barriers, and used the examples to suggest alternative methods to learning. We have included google earth as an alternative to support learners accessibility barriers.

- If learners have writing difficulties or learning disabilities, the journal response might be difficult.

- Suggestion: allowing video recorded reflections instead

We have made adjustments to the learning activity, notably suggesting that video or audio presentations could be made as an alternative to written journal responses. Perhaps students could create video or audio folders and post in a course LMS to communicate their findings about the BC Native Trees.

- Perhaps you might consider acknowledging more Indigenous knowledge and perspectives on trees

- Suggestion: Provide the indigenous names for key tree species

We have made adjustments according to this review, and both scientific names and indigenous names (mostly their SENĆOŦEN (W̱SÁNEĆ) name) to consider the cultural and scientific significance of these trees to the area where they grow..

Module 2: Tree identification Activity/Discussion

- Not only learning about different types of trees, your activity goes more in depth about the different characteristics of the trees which is amazing.

- Suggestion: Perhaps you might consider including the general environment where the types of trees are located.

We have added to the discussion portion of the activity where as a bonus students are able to research and add the location of where the tree they identified is usually located within BC! This can further allow students to understand their surroundings, as well as where they are likely to find the trees them and others have identified.

- This activity allows for a more personable and individual experience.

- Suggestion: Perhaps you might consider the option of a buddy system so that the students can learn with a friend, therefore it could make the activity more enjoyable.

We have added the option to work with a partner (no more than 2 people) in answering the discussion post, this allows a more enjoyable way, and a way to discuss with classmates. By making it an option to work with a partner, students are still able to work alone, if they feel more comfortable doing so.

Module 3: The Ecological Importance of Trees

- Correct me if I’m wrong but the reading assigned to the learners seems to be too high of a reading level.

- Suggestion: You could consider finding an appropriate reading level article to assign.

After further consideration, this is an article that uses basic language that is easy to understand, although there are few complicated words, it challenges readers to learn harder words and understand the concept better. There is also assistance from teachers and instructors that can help with more challenging words, if there is confusion, we have also provided a youtube video that demonstrates similar learning materials.

- Do you need to cite the leaf images used throughout the learning resource?

We have added citations for the leaf images we have used throughout our learning resource, these links take you directly to where the images were found, so students are able to explore other images and types of trees and leaves that they are interested in.

- We are wondering what kind of citation style you are using?

- Suggestion: I would consider providing a clear way of referencing ideas.

We have fixed our citations to follow APA formatting and citation style to provide more academic citations rather than simply links. This also provides a clearer citation list that many can understand, and the citation style stays consistent throughout the resource.

- Colour blind issues – they use colours to identify types of trees which wouldn’t work for people struggling with those types of issues

- Have you considered giving learners that struggle from colour blindness special glasses to make their experience accessible.

There is not much focus on identifying based on colours. However, we have now incorporated accommodations for colour blindness in “Specific Learning Needs” of the overview.

Resources:

CAST, Inc. (n.d.). The UDL guidelines. The UDL Guidelines. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Educational Resources. Forest Professionals BC. (2024, July 2). https://www.fpbc.ca/public-interest/student-resources/educational-resources/

ellameldrum99. (2025, March 5). Post your pictures and descriptions that you found!. Padlet. https://padlet.com/ellameldrum99/post-your-pictures-and-descriptions-that-you-found-w0tc8x50tlg7hkh1

ellameldrum99. (2025c, March 5). Why do you think trees are important to ecosystems?. Padlet. https://padlet.com/ellameldrum99/why-do-you-think-trees-are-important-to-ecosystems-89q82luynxce3cdb

FPBC. (n.d.-a). https://portal.fpbc.ca/Files/students/Gr4-5wonderfulworkingsofwood.pdf

Google. (n.d.). Tree Profile Journal Template. Google Docs. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1xQI5vEcnfEQh7dZBuhLfmncvFOUYkkDBzbSxMJjP9qc/edit?usp=sharing

Google. (n.d.). 2-3 ag Arnolds Apple (Tree identif).pdf. Google Drive. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1XcjdqTznjlS4Q6kCOvoh6BGw6QzMxPso/view

Greatbearrainforesttrust. (n.d.). https://dev.greatbearrainforesttrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Treebook.pdf

INaturalist. iNaturalist. (n.d.). https://www.inaturalist.org/

Julie. (2024, March 29). Pinecone coloring pages. Nature Inspired Learning. https://natureinspiredlearning.com/pinecone-coloring-pages/

Unpacking the proficiency scale- support for educators. (n.d.-b). https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/administration/kindergarten-to-grade-12/unpacking-the-proficency-scale-support-for-educators.pdf

Tree Bee. Tree Bee | Identify a Tree. (n.d.). https://treebee.ca/identify-a-tree/

Tree conservation. TOPIARYTREE.NET – TOPIARYTREE.NET. (2022, October 12). https://topiarytree.net/tree-conservation/?srsltid=AfmBOoppcYw8loVdAuXS447denAWioS_AcX_O6ZE5UAbrmVneIXqn7UE

Trees of Canada. Tree Canada. (2022, December 12). https://treecanada.ca/resources/trees-of-canada/#:~:text=Conifers%20are%20often%20called%20evergreens,are%20also%20known%20as%20hardwoods.

Why trees?. The Importance of Trees – Learn Value and Benefit of Trees. (n.d.). https://www.savatree.com/resource-center/tree-varieties/why-trees/

YouTube. (n.d.-a). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UnwMq1gGjhk

Assignment 2: Interactive Learning Resource Peer Review; Group B reviews Group I

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1kpl7IZdVoewgk3ObuqY_vXH8n34MGBfx2lbYPr8jjpE/edit?tab=t.0

Link to Doc of Peer Review: Assignment 2: Interactive Learning Resource Peer Review; Group B reviews Group I

To the members of Group I,

We appreciate the chance to review your interactive learning resource on digital health literacy. This feedback reflects our collective thoughts and aims to provide constructive insights to refine and enhance your educational materials. Thank you for your efforts and for considering our suggestions.

- Overview

General Appreciation

The topic you chose for your Interactive Learning Resource was very enjoyable; it is a very relevant and growing topic in our society that is commonly misconceived.

- Learning Context & Learners

Content Addition Suggestions

Looking further into your interactive learning activities, you may want to consider providing a small amount of content before getting learners to take the quiz and do the discussion; this way, learners will have the information necessary to decipher the differences between whether a health article demonstrates fake or real information. For example, potentially adding what cues or aspects of different articles to look out for when reading and analyzing articles, you mention having learners evaluate the sources based on credibility factors such as ‘author, credentials, citation, bias detection, etc.’ Having a short description of the content explaining what to look out for and how to assess this may be helpful for the learner. I know, especially for myself, that sometimes I forget what I should and shouldn’t look for in evaluating articles. Therefore, others may have similar experiences, so a refresher on what to assess for within the different articles may be beneficial.

- Learning Theory Rationale

Constructivism Learning Theory

Your interactive activities are practical and relevant. The quiz on misinformation, the exploration of health apps, and the data-based decision-making case study are all excellent applications of experiential learning.

Rationale

The alignment between your learning theory and your instructional strategies is strong. Your use of experiential learning nicely complements the constructivist framework, encouraging learners to reflect on real-world situations. It might be helpful to clarify how reflection is supported in each activity. For example, are there specific prompts or questions provided to guide the reflective process? Including this would ensure that learners engage more deeply with each phase of Kolb’s experiential learning cycle.

- Technology Choices & Rationale

Use of Brightspace Platform

Your decision to use Brightspace as the hosting platform is logical, given its accessibility features and integration capabilities. However, providing a visual representation or workflow of how students will navigate the platform could enhance clarity. For instance, a brief overview of a sample module with screenshots or a step-by-step guide on how to access key features (quizzes, discussions, resources) would help ensure that students can fully utilize the platform’s capabilities.

- Designing for Inclusion

In terms of inclusivity, your application of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles is commendable. Offering multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression reflects a strong commitment to accessible learning. You might consider providing a few examples of how learner choice will be implemented in assessments. For instance, will learners select from a menu of tasks, or are they able to propose their own method of demonstrating understanding?

- Conclusion and Summary

Overall, well done! Your interactive learning resource is well-structured, thoughtfully designed, and aligned with relevant learning theories. Hopefully, the comments above help you achieve excellence.

Reviewers from Group B for Group I: Ella Meldrum, Omid Izadi, & Kate Nelson

Peer Response Post #8

Hi Liam,

I really enjoyed your take on Open Pedagogy and how it shifts the traditional classroom dynamic. I especially connected with your reflections on your high school experiences with this teaching style—how it empowered you, yet also presented challenges. It’s a good reminder that while Open Pedagogy can hugely benefit motivated students, it might require more support for those who struggle with less structured approaches.

Your insights into Open Educational Resources (OER) struck a chord with me too. The way you explained their role in reducing costs and enhancing accessibility outlined the significant potential they have to make education equitable. I’ve noticed similar impacts in my own studies where OER have been a game-changer.

Also, your breakdown of Creative Commons licensing was super clear. It’s great to see how these licenses can support ethical sharing and innovation in education, something I’m trying to incorporate into my own projects.

Thanks for such a nuanced post—it gave me a lot to think about, especially on how we can better support all students in an open education framework.

Peer Response Post #7

Hi Marc,

Great post on Open Pedagogy! I appreciated how you highlighted the shift from traditional instructor-centered teaching to a collaborative, student-driven approach. Your examples of MIT OCW and OpenStax effectively showcase how Open Educational Resources (OER) can break down financial barriers and enhance access to education.

Your explanation of Creative Commons licensing also sheds light on how these licenses support ethical sharing and adaptation of educational content. It’s exciting to see how embracing open practices can lead to more inclusive and innovative educational environments.

Thanks for sharing these insights!

Peer Response Post #6

Hi Percy,

Great post on Open Pedagogy and the transformative power of OER! I really appreciated your example of the economics class collaboratively creating an open textbook, which beautifully illustrates the depth of understanding and ownership that Open Pedagogy can foster among students.

Your insights into the adaptability of OER, such as using global case studies for a more enriched curriculum, highlight their potential to make education more equitable and accessible. Additionally, your discussion on Creative Commons licensing provides a clear view of how these tools support ethical and responsible sharing of educational materials.

Thanks for sharing your thorough perspective on how Open Pedagogy can lead to more innovative educational practices.

Peer Response Post #5

Hi there!

Your comprehensive post on Open Pedagogy beautifully articulates how this approach not only shifts the educational paradigm but also empowers students and educators alike. I particularly enjoyed your discussion on how Open Pedagogy centers on student autonomy and interdependence, setting a foundation for a democratic and participatory learning environment.

You’ve detailed the profound impact of Open Educational Resources (OER) in democratizing education, making it more accessible and equitable. The practical examples you provided, such as using updated, relevant materials like data from the Covid-19 pandemic, illustrate the dynamic possibilities OER offers to tailor educational content to contemporary issues.

Your insights into the global trends and the historical context of OER adoption were enlightening, highlighting significant strides and ongoing challenges. It’s inspiring to see how these resources can transcend traditional barriers in education, providing equitable opportunities for all learners, irrespective of their circumstances.

Thank you for such an enlightening read and for the practical takeaways on applying Open Pedagogy in diverse educational settings!

Recent Comments