Posts in Category: EDCI 337 – Interactive and Multimedia Learning

Learning Reflection Report

Looking back on this course, what stands out most is how my understanding of multimedia shifted from a creative interest into a deeper pedagogical responsibility. With a sociology background and experience working closely with children, I entered the course aware that educational systems often prioritize speed, academics, and efficiency over learner wellbeing. What I didn’t expect was how strongly this course would intersect with my real-life learning; I began a new role supporting neurodiverse learners at the exact same time. The overlap made the lessons from this course feel not just relevant, but urgent and interconnected.

Revisiting the Plan: What I Learned & How I Met the Objectives

Across the comic, video series, and OER, I learned to design with the learner’s cognitive and emotional experience at the center. These challenges weren’t isolated tasks — they were steps in a progression that helped me move from ‘making content’ to ‘crafting supportive, accessible learning environments.

I met the course objectives by:

- Contextualizing learning in multimedia:

I became more attuned to how learners (of all ages) process information — visually, narratively, emotionally — and how multimedia can either support or overwhelm depending on design. - Applying multimedia principles:

Instead of applying principles mechanically, I began using them to make intentional choices about pacing, simplicity, and clarity. - Engaging in design thinking:

Empathy and iteration became central. I repeatedly asked: What does the learner need? Where might they struggle? How can I reduce overload? - Using storytelling effectively:

Storytelling became not just a format but a cognitive pathway into understanding — useful for both young learners and adults. - Producing varied prototypes:

Comics, videos, and an OER helped me experiment with multiple forms of design, each with its own pedagogical purpose. - Using GenAI appropriately:

I used AI for planning, drafting, and refining ideas — never for creating final assets. My creative decisions, scripts, visuals, and design structures were authentically my own.

Identifying the Turbulence: Challenges & Breakthroughs

One major challenge was balancing creativity with cognitive and emotional load. I tend to add more — more visuals, more narration, more detail — but I learned that restraint often serves the learner better. I had to shift my mindset from ‘complete’ to ‘clear,’ and from ‘impressive’ to ‘supportive.’

Accessibility was another area of turbulence. Starting this course at the same time as beginning work in a non-conventional educational setting meant I was receiving two parallel educations: real children showing me what accessibility looks like in practice, and this course showing me what accessibility looks like in design.

Peer feedback became essential in this process. Others pointed out details I had overlooked — colour choices that were too intense, captions that needed clearer pacing, or heading images that distracted rather than supported. This iterative feedback helped me refine accessibility not as a checklist but as a mindset.

By Challenge C, accessibility had become embedded in my design instincts — from chunking activities to simplifying layouts to choosing visuals that support rather than distract.

Evidence of Growth: How My Perspective Shifted

My perspective expanded far beyond children’s learning. I began noticing that multimedia supports all learners — at all stages of life. Learning does not end in childhood; it is a lifelong process shaped by pace, clarity, structure, and emotional readiness. As I watched my peers’ projects, many weren’t teaching “child-focused” content at all — they were teaching:

- how to learn patiently

- how to acquire new technical or physical skills

- how to navigate complex ideas at an accessible pace

- how to understand yourself or your environment more deeply

This made me recognize that the principles we applied — accessibility, coherence, storytelling, segmentation — are not age-specific. They are human-specific.

We are always learning something new at different levels of our lives, and multimedia gives us gentle, structured, digestible pathways into that learning.

This realization sharpened my sociological lens as well. I became more aware of the hidden curriculum embedded in multimedia — who feels included, who feels overwhelmed, and how design can challenge or reinforce systemic academic norms.

Next Destination: Using These Skills as a Future Educator

I now see multimedia as a powerful tool for educational equity across the lifespan. It can:

- slow learning down in a fast system

- support multiple processing styles

- help learners regulate and refocus

- visualize abstract concepts

- give adults and children alike accessible ways to explore new skills

As a future teacher, I can envision using:

- comics for SEL or social stories

- short videos to model routines, strategies, or calming techniques

- digital modules for mindfulness or academic support

- OER-style resources to collaborate with colleagues and support students’ families

Ultimately, this course taught me that multimedia is not about making learning ‘engaging’—it is about making learning humane. It provides gentle entry points, clearer explanations, and supportive structures for learners at any age and stage.

It is a bridge between creativity, pedagogy, and equity — and a way to help learners feel capable, grounded, and seen.

If learning is a lifelong journey, then multimedia is one of the few tools that can meet us at every stage—supporting us as we grow, adapt, and rediscover what it means to understand.

Challenge C: Substantive Post #2 – UDL

When I think about accessibility in learning design, especially through a UDL perspective, I’ve started to see it less as a checklist and more as a mindset. Accessibility, to me, is really about removing the mismatches between a learner and their environment—not “fixing” the learner, but adjusting the design so more people can participate meaningfully. CAST’s UDL framework has helped me understand that accessibility is rooted in flexibility: multiple ways to engage, multiple ways to take information in, and multiple ways to show understanding.

While working on my group’s Mindful Moments OER, I kept circling back to how teachers are learners too. An OER meant for classroom use shouldn’t only assume the needs of students—it should also support the teacher who might be squeezing in one minute at lunch to figure out how to guide a mindful breathing exercise. Some teachers might want to quickly skim text because their classroom is noisy at lunch. Others might benefit from listening to a short audio version if they have headphones. UDL reminds me that offering options isn’t extra work—it’s what makes learning actually reachable for more people.

In this course, we’ve talked a lot about how accessibility and multimedia can either lower barriers or accidentally raise them. Thinking about this while designing our prototype made me realize that “accessible design” doesn’t have to be complicated. Sometimes it’s just offering a clear layout, predictable navigation, and a choice of format. Ultimately, UDL pushes me to design with empathy, so that the people using the resource—teachers or students—can access what they need in the way that works best for them.

Mindfulness Moments in the Classroom

Updated: November 5th 2025

Authors: Michael Donkers, Taha Fareed, Kate Nelson

Brief Project Intro

We have chosen this topic because we all previously worked on topics that connect to this topic in one regard or another (Michael and Taha did their Challenge B on understanding the mind, Michael’s Challenge A was on the importance of exercise, Kate did her Challenge B on Mindful Moments). Combining these ideas together, we aim to create an OER that can be used by both teachers and learners to the concept of “mindful moments” which we would describe as being very short little movement breaks throughout the day that can help to shift our attention, regulate our emotions and ease the mind.

FINAL DESIGN COMING SOON

THE PROCESS

Understand (Discover, Interpret, Specify)

DESCRIBE THE CHALLENGE:

Many educators struggle to understand that mindfulness isn’t something that can just be added as part of a students day and expect that it’s going to take effect. How it is used throughout the day, when it is used and why it is used are all very important questions that need to be answered simply put there just isn’t enough time in the day for most educators. The solution? We aim to create a resource that will help educators to answer all these essential questions so that mindfulness can authentically be part of their day.

CONTEXT AND AUDIENCE:

Audience

Our target audience for our OER is ideally suited for educators that are working with elementary and middle school students, however the activities shared in this resource can easily be adapted to be suitable for most age groups. It is also a great resource for students such as ourselves that are studying in the field of education as well as new teachers looking to add more into their social-emotional learning toolkit. The target audience is those that have perhaps heard of the term mindfulness and have some degree of background with it but aren’t at a point where they feel like they could lead it with confidence or understand how it ties into classroom regulation.

Needs

The key to meeting the needs of the students is to demonstrate mindfulness to them in ways that don’t take away from the lesson being taught, these demonstrations of different techniques should just blend in with the rest of the day without feeling out of place. Our resource will showcase how different movements and activities can be adapted to work in just about any classroom. Through our resource we will provide teachers and students the opportunity to show attention to providing support, catering to different emotions seen in classrooms across the board and demonstrating an eagerness to learn through practising mindfulness.

Goals

In terms of goals, we have a few that come to mind as we design his OER on mindfulness and this simply begins with helping educators to understand not only what it is but why it is so important for students. There is a fine balance between practising calm mindfulness and using movement as a way to be mindful and so we set out to show how the two can be used together. We also aim to provide context by providing examples of how these different techniques can be used in day to day classroom activities.

Motivation

We live in a very digital driven world and so classrooms are running at a higher pace than we have ever seen before. This makes it difficult for teachers to feel like they have a handle on the situation and it is in all honesty, rightfully so, overwhelming. As a group, we feel there is a solution to this and that is to provide teachers and students with a tool that they can keep in their toolkit that will serve them in life beyond the classroom. Providing them the resources to practice mindfulness is highly motivating and will create a more positive learning environment.

POV STATEMENT:

A teacher that is lost in how, when and most importantly why they should use mindfulness in their classroom needs a resource that educates them on mindfulness so that students are able to regulate their own emotions to create a more positive learning experience.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

- Learners will be able to understand that mindfulness is about being present in the moment without regard for other variables

- Learners will be able to demonstrate how through engaging in mindfulness activities their focus has improved and they are much more emotionally regulated

- Learners will be able to feel confident in sharing how mindfulness affects their own emotions and share with others their own techniques they have developed

- Learners will be more reflective on how mindfulness can be adapted to meet the learning needs of many different diverse students and teachers

Plan (Ideate, Sketch, Elaborate)

IDEATION:

We decided that the OER should feel very easy to pick up and use especially during busy times. While creating Phase 1 we noticed that teachers need really short activities, clarity on when to use them, and language that helps students connect the activity to an emotion. Our main idea for this challenge is a small set of “Mindfulness Moments” organized by a purpose such as focus, calm, reset and time such as 30 seconds, 1 minute, 2 minutes.

While brainstorming we came with 3 possible delivery formats:

- Slide-based OER: one mindfulness moment per slide

- Short video: such as challenge B maybe show an animation or video of the teacher explaining a concept with animations so students are able to follow along

- Quick references: quick notes the teacher can print and stick to their desk like “if students are restless do X” or “If students are low energy do Y”

After brainstorming our ideas we chose between a mix of 1 and 2. So our Final OER would be a set of short and repeatable mindfulness activities that explain why to the teacher and how to the students

STORYBOARD OR SCRIPT:

Scene 1 (Intro, Signaling):

- Title: “Mindfulness Moment: Reset”

- Narration: take a quick mindfulness moment to reset our brains

Scene 2 (Why we’re doing this, Coherence):

- Have a brain, heart, and clock in the scene (cartoon)

- Narration: “This helps your body slow down so it’s easier to focus on the next activity.”

Scene 3 (Posture, Modality):

- Cartoon character sitting upright, feet flat.

- Narration: Sit with your back straight, put both feet on the floor, and rest your hands

Scene 4 (Breathing, Temporal Contiguity):

- A breathing circle like something from a “relaxation video” from youtube

- Narration: “Breathe in and hold for 3 seconds and breathe out, repeat 3 times)

Scene 5 (mindfulness cue, Segmenting):

- Narration: As you breathe, notice how your body feels loose, your shoulders drop down, your face gets relaxed…)

Scene 6 (Return to task, UDL)

- Add icons of notebook and laptop

- Narration: Bring your attention back to your current task and don’t be afraid to use this whenever needed.

PRINCIPLES APPLIED:

When we were planning out our mindful moment activity, we tried to be thoughtful about a few multimedia learning principles that would make the experience clear and easy for students. We used Signaling by keeping the title and purpose very straightforward so teachers and students know right away what the activity is about. We also followed Coherence by choosing only simple visuals (like a brain or breathing cue) instead of anything busy or distracting, since the whole point is to help students settle. For Modality, the idea was to pair short spoken instructions with matching visuals so students can process the steps without getting overloaded by text. Lastly, we used Segmenting by breaking the activity into smaller steps, which should make it easier for teachers to guide and for students to follow at their own pace.

Create and Share the Prototype

The prototype for our Open Educational Resource (OER) has been created using Google Sites. The goal of this prototype is to provide a simple, accessible first version of our “Mindful Moments in the Classroom” resource—one that demonstrates the structure, visual design, and layout of the final OER.

This prototype includes:

- A Home page introducing the purpose of the OER

- A Teacher Resources section with background information on mindful moments and guidance on choosing the right activity

- A Mindfulness Moments section with one completed activity page (“Mindfulness Moment: Reset”), based on our group’s storyboard

- A dedicated Open License page using the CC BY 4.0 license

This prototype highlights the core design principles we aim to apply in the final version: clarity, simplicity, accessibility, and alignment with mindfulness practices. Future iterations would include additional mindful moment activities, visuals, and potentially short video demonstrations.

Prototype Website Link:

Challenge B: Mindful Moments with Sunny & Brain: Videos

A three-part educational video series for kids (and the kids at heart)

Updated: October 24, 2025

Author: Kate Nelson

This project grew out of my work with children who sometimes have big feelings and small words to match them. I wanted to design something short, kind, and clear – something that could help kids slow down for a moment and understand what’s going on inside.

So I created three one-minute videos about mindfulness:

- What is Mindfulness?

2. How Breathing Helps the Brain

3. Try a Mini Mindful Pause

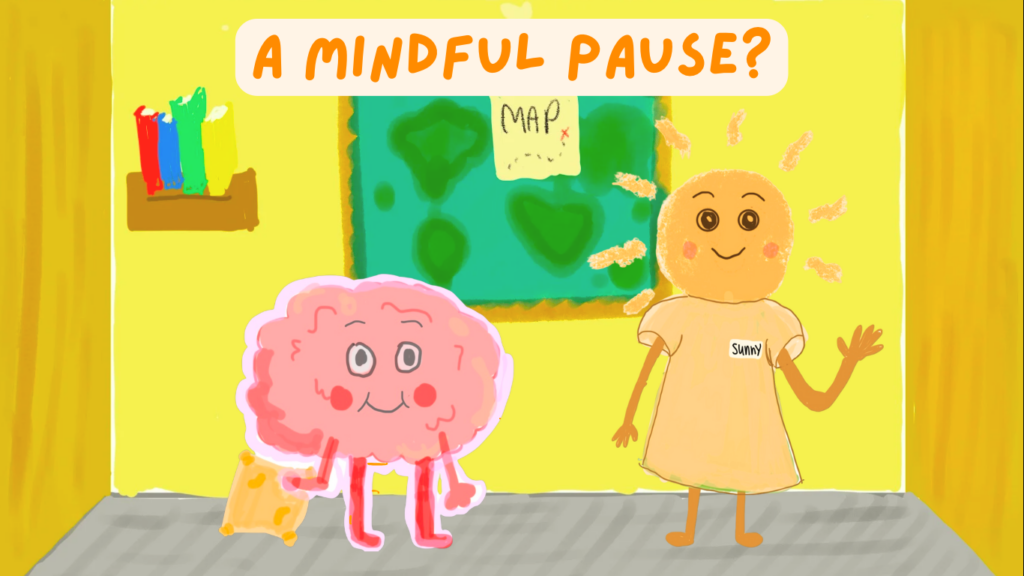

Each video stars either Sunny, a curious little student, and Brain, her cheerful pink sidekick who’s trying its best to stay calm under pressure and teach us how to relax during overwhelming moments.

My goal was to help Grades 2-5 learners understand mindfulness through gentle storytelling, simple visuals, and calm narration. The videos were created with Canva Video Editor, using my own iPad drawings exported through Photo Booth as transparent graphics. Some Canva-provided animations and sounds helped bring the characters to life.

Understand

DESCRIBE THE CHALLENGE:

Children need accessible ways to understand and regulate their emotions through mindfulness – especially in everyday classroom or after-school settings.

CONTEXT AND AUDIENCE:

These videos are designed for children aged 7-11, but they’re flexible for teachers and parents to use too. Many kids this age are just beginning to name emotions like frustration, excitement, and worry.

In typical cases, learners may struggle with patience or transitions (like cleaning up or leaving recess). In extreme cases, students with anxiety, ADHD, or developmental disabilities might find emotional regulation overwhelming.

These short videos meet them halfway – using familiar rhythm of short-form media (think Youtube Shorts or TikTok) while shifting the tone to be slower, softer, and more mindful.

POV STATEMENT:

A child who feels upset or overstimulated needs a calm, friendly video guide that helps them pause, breathe, and name what’s happening inside.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

The learning goals for this series are to help Grades 2-5 learners understand mindfulness as “kind attention to the present moment,” recognize in simple terms how slow, steady breathing can calm both the body and the brain, and practice a brief mindful pause independently. Along the way, a quieter set of aims runs underneath: building emotional vocabulary, encouraging gentle self-check-ins (“how do I feel right now?”), and nudging metacognitive awareness so students can notice what helps them refocus. Each video – definition, explanation, and try-it, was designed backward from these objectives so every scene, caption, and animation supports clarity, calm, and carryover into real classroom moments.

Plan

IDEATION:

The idea for this project was first sparked during a yoga class I took, when the instructor asked us to imagine ourselves as children – too upset to explain what was wrong – and to think about how much better we might have felt if we had known how to pause and breathe through the problem. As someone who works with children every day, that moment inspired me to create a resource that helps kids understand that kind of mindful pause. From there, I began doodling – a girl sitting at her desk, which became the early base for the second video – followed by the expressive little Brain character, and later, a simplified boy version that worked better for animation. I drew inspiration from educational explainer videos and resources by Headspace, AsapScience, and Peekaboo Kidz, all of which balance playfulness with clear learning. My most promising prototypes were the boy-and-brain animations, which captured mindfulness in a warm, relatable, and gently humorous way.

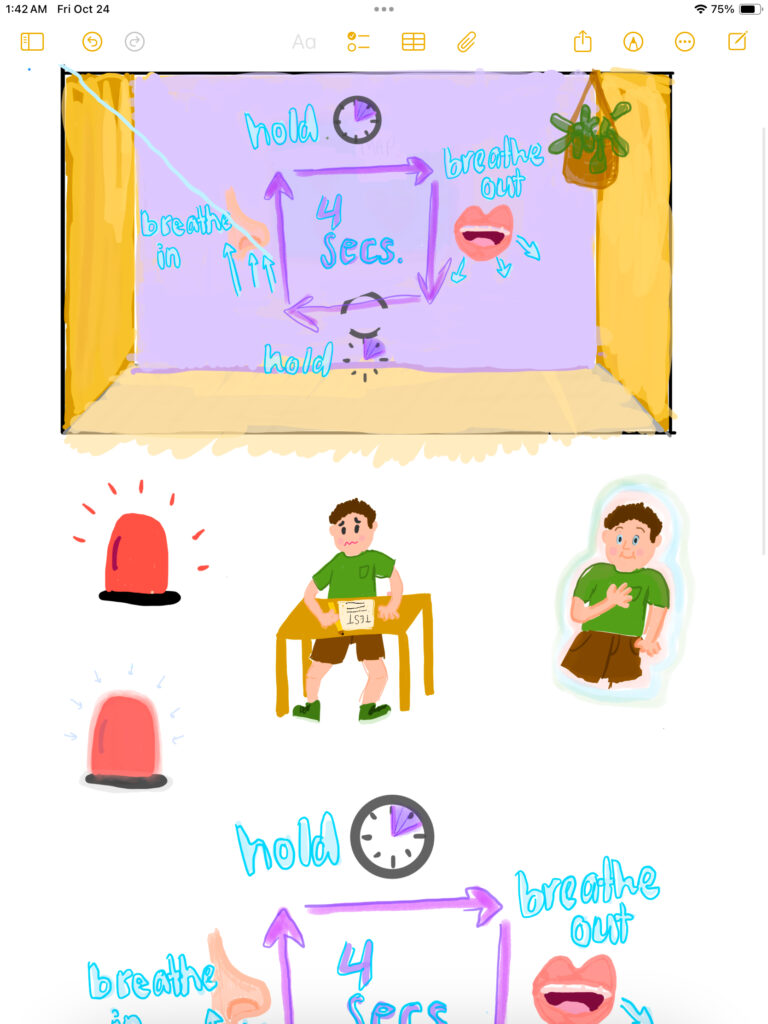

STORYBOARD OR SCRIPT:

My storyboard and script were created through hand-drawn scenes designed to express calmness, emotion, and learning through gentle visuals. Each frame was drawn on my iPad and sent through the Photo Booth app to create transparent PNGs for animation in Canva, where I layered, timed, and animated the drawings to match the narration.

The second video, “How Breathing Helps the Brain,” introduces Brain and a boy sitting at his desk, feeling anxious about a test. A red alarm beside him represents the brain’s stress signal—its “alarm” going off when we feel worried or overwhelmed. When Brain appears, he explains how breathing helps calm this response, connecting the science of mindfulness to the body. Shelley Murphy’s Fostering Mindfulness (2019) was an important reference in shaping this video. Her discussion of how mindful breathing supports the brain’s emotional regulation and attention systems helped me frame this explanation in an age-appropriate way. Murphy’s work also guided the box breathing (or square breathing) sequence that follows, where Brain leads the boy—and the audience—through four counts of inhaling, holding, exhaling, and holding again. The visual cues of arrows, clocks, and breath icons were designed to mirror Murphy’s emphasis on pacing, rhythm, and embodied mindfulness.

The final video, “Try a Mini Mindful Pause,”, builds on that foundation with Sunny and Brain co-leading a short, natural breathing exercise. Unlike the structured square breathing in the previous video, this sequence focuses on steady, rhythmic breathing—encouraging children to pause, breathe, and refocus in real time.

Throughout the storyboard and scripting process, I prioritized warmth, simplicity, and emotional safety. Soft colours, friendly character designs, and gentle narration were all chosen to help children feel calm and included. My goal was not only to teach what mindfulness is, but to let viewers experience how mindful breathing can change how we feel inside.

PRINCIPLES APPLIED:

Throughout this project, I applied Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning to guide every design decision. The Modality Principle was central: I paired clear, friendly narration with visuals so children could process information through both auditory and visual channels. The Coherence Principle shaped my art style – I simplified backgrounds and used calm colours so attention stayed on Sunny and Brain (the guides).

The Segmenting Principle helped structure the series: each video lasts around one minute and focuses on a single idea: (1) What mindfulness is, (2) How breathing helps the brain, and (3) Trying a mindful pause. This ensured the learning content remained digestible and focused, reducing cognitive overload for younger viewers.

Accessibility was another key consideration. To support learners with hearing impairments – or anyone who prefers or requires text support, I included captions that matched my narration closely. This decision aligns with inclusive design practices and ensures that each video is understandable regardless of hearing ability, language background, or listening environment. My goal was to make the series equally accessible to children learning English as a second language or those who simply engage better with visual text reinforcement.

The Personalization Principle guided my tone of voice: calm, conversational, and gently playful — mirroring the way I speak with children at work. The Voice Principle was maintained through my own natural narration rather than a generated voice, to preserve warmth and authenticity.

Finally, Shelley Murphy’s Fostering Mindfulness (2019) informed both the content and pacing. Her writing on how mindful breathing supports the brain’s emotional regulation and focus helped me design scenes where children could practice what they were learning. The result is a series that blends the educational strength of multimedia learning with the emotional safety and accessibility of mindfulness practice.

PEER FEEDBACK:

The feedback I received throughout the Challenge B process was generous and encouraging, offering both practical and reflective insights that helped shape my final videos. My first round of feedback, from peers like Caelan, Emma, and Charlie, focused on my ability to connect personal experience with theory. They appreciated how I linked my own mindfulness practice to Mayer’s multimedia principles, especially pacing, narration, and visual clarity. Their comments reminded me to include more concrete examples of how those principles would appear in my own work — an idea that carried forward into my prototype.

During the prototype review stage, peers like Sai and Julia offered feedback that deepened my design thinking. They highlighted the strength of my structure and calm tone, noting how the short, themed segments reflected the Segmenting Principle and created a peaceful learning environment for children. Julia also encouraged me to bring more of my early sketches and visuals into the prototype phase — advice that influenced how I presented my progress in Substantive Post #2. Sai suggested I add clearer signalling to direct viewers’ attention, which inspired subtle design choices like motion cues and breath indicators in the final videos.

Finally, feedback on Substantive Post #2 from Therese, Tanuj, and Alexis helped me articulate how iteration connects to growth. They appreciated my reflection on design as a looping process and how I built confidence from feedback. Their encouragement to expand on revision and process led me to write more openly about my creative learning curve — including the decision to simplify my character design and clarify my audience. Overall, my peers’ comments helped me see my videos not only as creative media but as structured, educational tools that model mindfulness through both form and content.

Reflect and Refine

Note: This project was completed individually, so this reflection represents both the design process and my personal learning experience.

Looking back on this project, I’ve learned how much design is really about listening — to feedback, to your audience, and to the feeling you want the learner to leave with. When I first started, I was thinking mainly about how to make something creative and visually engaging. But as I moved through the phases of feedback and revision, I began to see how design can also be an act of care — a way to meet learners where they are, and to build calm, curiosity, and understanding through small, intentional choices.

Working independently meant that every stage of the process was mine to navigate, from developing the idea and drawing the characters to narrating, editing, and revising. It was definitely challenging at times, but it also gave me freedom to follow my instincts and make something that feels true to my voice. One of my biggest takeaways was how simplifying the visuals actually made the message stronger. The first version of my “girl at the desk” drawing was full of tiny details that looked nice but made the scene too busy to work with. When I redesigned it into the “boy at the desk” version, everything became easier to animate and more focused — it matched the calm, gentle tone I wanted children to feel.

I also drew inspiration from Shelley Murphy’s Fostering Mindfulness, which helped me better understand how breathing affects the brain and emotions. Her writing on mindful breathing guided both the structure of the second video and the inclusion of “square breathing” (or box breathing) as a simple, teachable practice. I wanted the science of the brain and the act of breathing to connect — not just as information, but as something kids could actually try for themselves. That’s why the sequence of Brain and the boy breathing together became one of my favourite parts of the whole project.

Throughout all three videos, I was also really intentional about accessibility. I made sure to include captions that matched my narration so that any viewer — whether they have a hearing impairment, prefer reading to listening, or just need quiet time — could still follow along and understand the message. Making something that felt inclusive and gentle was important to me, because mindfulness should be for everyone, regardless of how they experience the world.

As someone who hopes to teach this same age group one day, I can easily imagine using a resource like this in a classroom. I’d love to play these videos as part of a morning routine or after a tricky moment, and then talk with my students about what mindfulness means to them. Having something visual, short, and calm that we could revisit together would make those conversations feel more accessible and natural — like saying, “let’s breathe through this together” instead of just “calm down.” I think that’s what I’ve learned most from this process: mindfulness and design both work best when they invite people in, not when they tell them what to do.

If I were to keep developing the project, I’d like to explore more interactive or personalized mindfulness activities that let kids choose what works best for them. But for now, I’m really proud of how these videos turned out. They’re calm, curious, and kind — exactly the kind of energy I’d want to bring into my future classroom.

References:

ASAPScience, (video), “The Scientific Power of Meditation”, on Youtube. Written by: Rachel Salt, Gregory Brown and Mitchell Moffit. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aw71zanwMnY

EdTech Uvic, EDCI 337: Theories of Multimedia Learning. https://edtechuvic.ca/edci337/2025/09/05/theories-of-multimedia-learning/

Gordon, T., & Borushok, J. (2019). Acceptance and mindfulness toolbox for children and adolescents : 75+ worksheets and activities for trauma, anxiety, depression, anger and more. PESI., http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uvic/detail.action?docID=6260894.

Headspace, Mindfulness with Kids. https://www.headspace.com/content/topics/mindfulness-with-kids/99?origin=content_hub_home

Murphy, S. (2019). Fostering mindfulness : Building skills that students need to manage their attention, emotions, and behavior in classrooms and beyond. Pembroke Publishers, Limited.

Peekaboo Kidz, (video), “The Five Senses”, on Youtube. Written by: Peekaboo Kidz. Produced by: Rajjat A. Barjatya. Script Writer: Sreejoni Nag. https://youtu.be/q1xNuU7gaAQ?si=XPKMC1m7bX2H_awz

Substantive Post #2: Reflection on the Design Process

When I think about the design process, I picture it as a loop rather than a line. Each stage, understanding, planning, trying, and reflecting, teaches me something new and reshapes what comes next. I’ve realized that design is less about reaching a polished endpoint and more about responding to feedback and discovery. The Double Diamond model from our course helped me visualize this pattern: the first diamond encourages open, divergent exploration, and the second guides convergence toward clear, purposeful choices. It connects closely with Backward Design, which reminds me to start with the end goal in mind – what I want the learner to understand, feel, or take away – before I get too caught up in the visuals.

Challenge A: Comics

In Challenge A, I designed a short comic to help children, especially those with developmental disabilities, recognize and express emotions. Using AI-generated imagery and colour, I explored how visual cues can communicate feelings. Through iteration, I simplified panels, adjusted pacing, and emphasized empathy over detail, which helped me learn that clarity and warmth reach young readers more effectively than complexity.

Challenge B: Videos

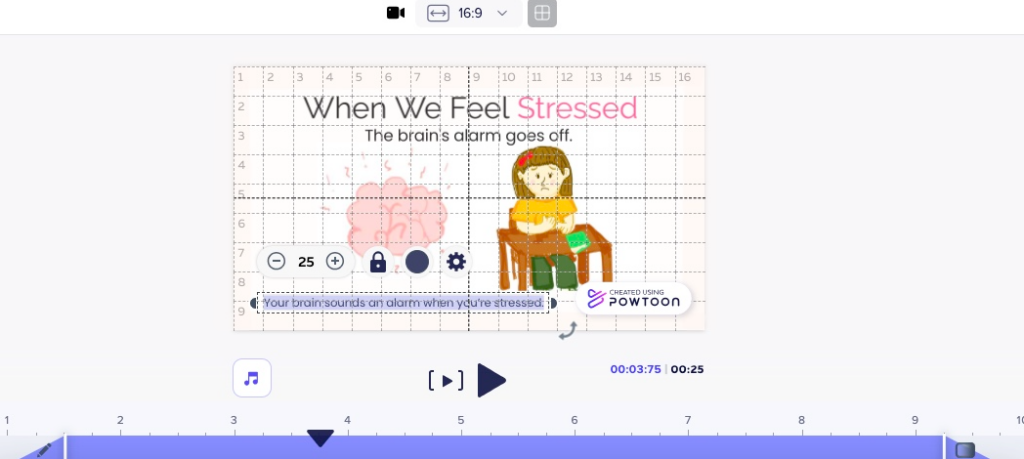

That learning flowed directly into Challenge B, where I’ve been layering movement, sound, and timing into the design process. Using Powtoon and my iPad drawings, I’ve been building short mindfulness videos inspired by Headspace and ASAPScience. I’m also learning the practical side of design—editing animations, drawing scenes, and managing files across multiple devices and workflows. Now that I’ve received peer feedback on my prototype, I plan to refine my visuals, narration, and pacing further. Each round of revision feels like an opportunity to grow both creatively and technically, turning experimentation into confidence and curiosity.

To visualize part of my creative process, the screenshot below captures an early stage of my video prototype, where I combined my own drawings with timing, narration, and accessibility features using Powtoon.

Challenge B: Prototype

Mindful Moments: Understanding and Practicing Mindfulness for Kids (Grades 2-5)

Author: Kate Nelson

Updated: October 12, 2025

Brief Project Intro:

I am creating a short educational video series called “MIndful Moments” to introduce mindfulness to children in Grades 2-5. I am working independently on this project.

I chose this topic because, in my experience working with children across different learning environments, I’ve consistently noticed how difficult it can be for them to calm down and express their emotions when upset. There are many existing resources that support families and educators in introducing mindfulness to children and helping them approach challenges such as trauma, anxiety, and stress. Two that have particularly inspired me are Headspace for Kids and Families – which offers guided meditations for calming down, managing anxiety, and winding down, and The Acceptance and Mindfulness Toolbox for Children and Adolescents by Gordon and Borushok – which provides developmentally appropriate exercises for teaching emotional regulation and awareness.

My goal for this project is to design three one-minute videos that blend education and guided practice, in a mix of explainer and how-to videos. I want them to feel approachable, calm, and relatable for children across this age group – simple enough for younger students but not too ‘young’ for older ones.

In this process, I’ve been experimenting with combining Powtoon animations and hand-drawn iPad illustrations while narrating in my own voice. The process has required a lot of thought around pacing, tone, and accessibility to make sure the concepts are engaging and meaningful for students.

Understand (Discover, Interpret, Specify)

DESCRIBE THE CHALLENGE:

Many children struggle to regulate emotions, calm their bodies, and express how they feel during stressful moments. They need simple, accessible strategies to practice mindfulness and learn emotional self-regulation.

CONTEXT AND AUDIENCE:

My intended audience for this project is children in Grades 2-5, typically ages 7-11. This age group is often curious, imaginative, and increasingly aware of their own emotions and experiences, which makes it a great stage to begin exploring mindfulness in a simple, age-appropriate way. The videos will use calm narration, storytelling, and clear visuals to make mindfulness concepts approachable and enjoyable rather than instructional or overly serious.

Within this age range, there’s a wide variety of learners. Typical cases might include children who are learning how to handle everyday frustrations, distractions, or feelings of stress. More extreme cases could include children who experience higher levels of anxiety, emotional sensitivity, or neurodiverse traits such as ADHD or autism spectrum conditions. The videos are not meant to serve as therapeutic tools for these experiences but instead offer gentle, accessible introductions to breathing, awareness, and calm focus – ideas that can benefit a range of learners.

Although the project is primarily designed for children, I hope that teachers or families may see value in sharing it with their own students or children. My intention isn’t to provide expert advice, but to create a fun, creative, and meaningful entry point into mindfulness – something that helps kids pause, breathe, and reflect for just a moment in their day.

POV STATEMENT:

An elementary student who feels overwhelmed or frustrated during the school day needs simple, guided mindfulness strategies so that they can calm their mind and body, refocus, and communicate their emotions more effectively.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

The “Mindful Moments” video series is designed to help children begin understand and practice mindfulness in a simple and engaging way. The main learning objectives are for learners to recognize mindfulness as paying attention to the present moment with curiosity and kindness, understand how breathing can influence the brain and body during moments of stress, and try short mindfulness activities – like breathing exercises or sensory awareness – to calm their minds and refocus.

Beyond these surface goals, the videos will also aim to promote deeper learning outcomes. By gently encouraging reflection, children can begin to notice how they feel before and after practicing mindfulness, helping them build self-awareness and patience. These ‘secret’ goals include developing an early sense of emotional regulation, curiosity about their own thoughts and feelings, and empathy for others who might experience similar emotions.

Plan (Ideate, Sketch, Elaborate)

IDEATION:

I brainstormed ways to present mindfulness in a short, meaningful format that balances explanation and participation. I decided on three different concepts expressed in each video:

- What mindfulness is,

- How breathing impacts the brain, (with inspiration and learning from the ASAPScience video)

- How to practice mindfulness in the moment.

My most promising prototype uses narration and illustration together, allowing the viewer to listen, watch, participate. The tone is warm and calm – something a child could follow independently or with an adult.

STORYBOARD OR SCRIPT:

Video 1 – “What is Mindfulness?”

- Intro: “Have you ever felt your mind racing or your body buzzing?” -> animation of a fast-moving stick figure.

- Middle: Explains mindfulness as paying attention to the present moment, noticing sounds, sensations, and breathing.

- End: “Try noticing one thing around you right now – what do you see or hear?”

Video 2 – “How Breathing Helps Your Brain”

- Intro: “When we’re stressed, our brain thinks there’s danger – even if there isn’t.”

- Middle: Illustrate a brain and lungs, explaining how slow breathing calms the body.

- End: Guide viewers through one cycle of box breathing (inhale 4, hold 4, exhale 4, hold 4).

Video 3 – “Try a Mini Mindful Pause”

- Intro: “Let’s try a one-minute mindful pause together.”

- Middle: Guide a “3-2-1” awareness practice: “3 things you can see, 2 things you can hear, 1 you can feel.”

- End: “Take one deep breath. How do you feel now?”

PRINCIPLES APPLIED:

In designing the “Mindful Moments” video series, I am applying several of Mayer’s Multimedia Learning Principles to make the content clear, engaging, and accessible for children. The coherence principle guides my decision to include only visuals that directly support the narration, keeping the screen simple and free of distractions. Following the modality principle, I will use my own narration paired with illustrated visuals rather than on-screen text, allowing learners to process information through both visual and auditory channels without becoming overloaded. The signalling principle will appear through the use of arrows, highlights, and pacing to draw attention to key concepts, such as the rise and fall of the breath or the difference between a tense and calm brain. I will also apply the segmenting principle by dividing information into three short, focused videos – each covering one main idea into manageable, one-minute segments. Finally, the personalization principle will shape the narration style: calm, friendly, and conversations, modeling mindfulness and creating a relaxed tone that feels approachable for students. Together, these principles will help make the videos more effective by maintaining focus, supporting comprehension, and encouraging active participation in each mindfulness practice.

- Explain the principles guiding your solution, referencing the Educational Multimedia Design Principles explicitly.

Important Note: Complete drafts of Phases 1 and 2 before starting your prototype.

Create and Share the Prototype

At this stage, I have not yet created the videos themselves, but I’ve outlined the structure, tone, and style that will guide their development. My prototype consists of the scripts, concepts, and design plans for each of the three short videos, which I plan to bring to life using Powtoon and my iPad illustrations with Apple Pencil for animation. Each video will include narration by me, along with pauses and counting to encourage viewers to follow along in real time.

The third video, “Try a Mini Mindful Pause,” will likely serve as the first completed example for my final submission, since it includes a practical mindfulness exercise that can be tested for flow and timing. Although I’m submitting this prototype later than planned, I’ve put significant thought and care into the design process so far. I’m looking forward to feedback from my peers on how the concept, pacing, and narration style might best support learning and engagement in the final product.

References:

ASAPScience, (video), “The Scientific Power of Meditation”, on Youtube. Written by: Rachel Salt, Gregory Brown and Mitchell Moffit. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aw71zanwMnY

EdTech Uvic, EDCI 337: Theories of Multimedia Learning. https://edtechuvic.ca/edci337/2025/09/05/theories-of-multimedia-learning/

Gordon, T., & Borushok, J. (2019). Acceptance and mindfulness toolbox for children and adolescents : 75+ worksheets and activities for trauma, anxiety, depression, anger and more. PESI., http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uvic/detail.action?docID=6260894.

Headspace, Mindfulness with Kids. https://www.headspace.com/content/topics/mindfulness-with-kids/99?origin=content_hub_home

Challenge B: Substantive Post #1

“The Scientific Power of Meditation” by ASAPScience

Updated: October 11th, 2025

Author: Kate Nelson

As someone who practices meditation regularly, often using apps like Headspace or attending yoga classes to help me breathe, reflect, and calm my nervous system, I’ve definitely felt the effects in how I respond to stress and overwhelming situations. However, I have never fully understood the scientific benefits of meditation for everyone who practices it. This video, “The Scientific Power of Meditation” by ASAPScience, really helped me clarify that and ‘put a face to the name.’

I love how simple the explainer video is to understand, with clear visuals, a clear voice, and a touch of humour that keeps things engaging without losing focus. The animation style makes complicated ideas about the brain easy to follow and remember, which is something I hope to reflect in my own Challenge B project.

From the lens of Mayer’s Multimedia Learning Theory, the video does a great job balancing visual and auditory information. The narrator speaks as illustrations appear on screen, showing the modality principle in action. The coherence principle is present since every visual directly supports the narration, and the signalling principle appears through arrows and highlights that guide attentionto important details. The pacing uses the segmenting principle, dividing the science into small, understandable chunks. Finally, the casual and friendly narration shows the personalization principle, addressing potential audience emotions and helping viewers connect to the topic.

Overall, this is an amazing example of how simplicity, pacing, and a bit of humour can make learning something like meditation both enjoyable and meaningful.

References:

ASAPScience, (video), “The Scientific Power of Meditation”, on Youtube. Written by: Rachel Salt, Gregory Brown and Mitchell Moffit. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aw71zanwMnY

Headspace, meditation (webpage, app). https://www.headspace.com

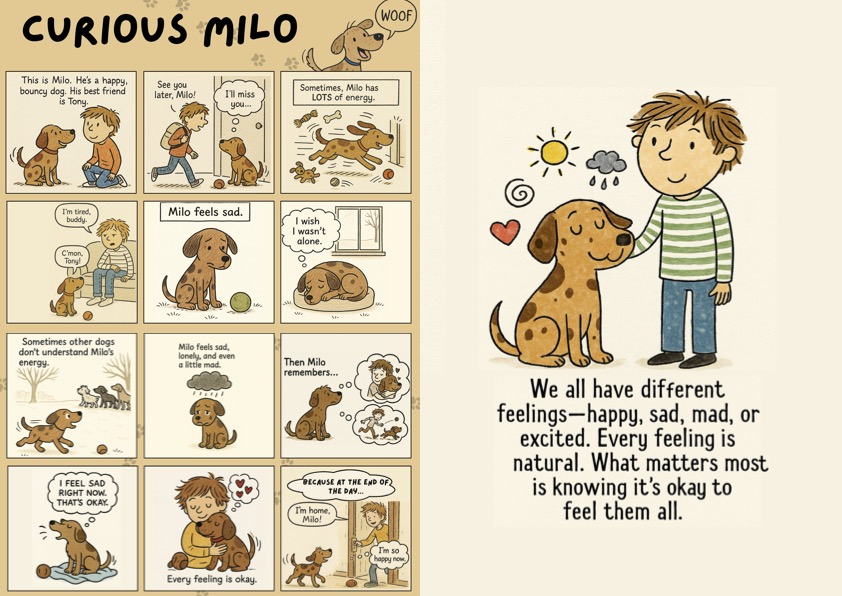

Substantive Post: Comics as Tools for Emotional Learning

As I worked through Challenge A: Comic, I kept circling back to the idea that comics don’t need to be complicated to be powerful. One resource that gave me a good jumping-off point was Chris Grady’s wholesome comics, better known as @Lunarbaboon on Instagram. His panels are simple, but the faces tell you almost everything you need to know — the expressions often carry more weight than the words beside them. It made me think about how a character like Milo could do the same for children on the autism spectrum, who may not always connect to their own emotions but can often empathize when they see them reflected in someone else.

I’ve also always been a fan of Garfield books — a lasagna-loving cat dealing with all the day-to-day musings of being Jon’s pet. Garfield is grumpy, sarcastic, occasionally elated, and always relatable (especially on Mondays). As lighthearted as they are, those comics show the ebb and flow of feelings in ways kids can easily grasp. Taken together, Garfield and @Lunarbaboon reminded me that characters don’t need to be human to be emotionally honest — pets and cartoon figures often work best.

Tool-wise, I started out planning to draw my comic on my iPad with Procreate and my Apple Pencil. But to keep Milo’s expressions consistent, I used AI through ChatGPT/DALL·E to generate the images. I then polished and arranged them in Canva and Google Docs. That mix of inspiration and tools helped me keep the comic simple, expressive, and emotionally meaningful.

Challenge A: Comic – Curious Milo: Teaching Kids That All Emotions Are Natural

Curious Milo (Educational Comic Project)

Helping Children Recognize and Accept Their Feelings

Updated: September 20th, 2025

Authors: Kate Nelson

This comic project is Curious Milo, a 13-panel educational comic designed to help children on the autism spectrum recognize and normalize their emotions. The comic follows Milo, a playful and relatable dog, as he experiences a range of feelings — from excitement and joy to sadness and disappointment — and models how all emotions are natural and okay. Structured across clear, sequential panels, the story uses simple narration, speech bubbles, and thought bubbles to make emotional awareness accessible, engaging, and child-friendly.

Understand

CHALLENGE:

Children on the autism spectrum often struggle to recognize, communicate, or express their own emotions, even though they may show empathy when others display feelings. This project uses a relatable dog character to help children understand that all emotions are natural and okay, making emotional awareness more approachable and engaging.

CONTEXT AND AUDIENCE:

Audience (Typical and Extreme Cases):

This project is designed for children on the autism spectrum, primarily between the ages of 6 and 10. Some may simply need extra support recognizing and labeling feelings, while others may depend heavily on visuals or non-verbal methods.

Needs:

In my work with children on the spectrum, I’ve noticed they often find it easier to empathize with a character, animal, or someone else showing feelings than to recognize those same emotions in themselves. They need clear, safe, and playful ways to externalize emotions. Milo, a bouncy and relatable dog, provides that lens by modeling a range of feelings.

Goals:

The goal is to help children see emotions as natural and temporary. For some, that means naming or pointing to a feeling, while for others it might simply be feeling safe enough to acknowledge them.

Motivations and Factors:

Demographically, the audience is young school-aged children supported by teachers, caregivers, and families. Psychographically and behaviourally, they respond best to clear visuals, predictable stories, and relatable characters rather than abstract explanations. This project aligns with those needs by keeping the story simple, structured, and engaging.

POV STATEMENT:

A child on the autism spectrum needs a safe and relatable way to see emotions modeled clearly so that they can begin to recognize, accept, and express their own feelings.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

Main objective:

Children on the autism spectrum will be able to recognize their feelings in a healthy way by learning that all emotions are natural and okay.

Sub-Objectives:

- Identify at least four core emotions (happy, sad, lonely, mad).

- Relate personal experiences to Milo’s story (e.g., “I feel like Milo when…”)

- Practice expressing emotions through words or non-verbal strategies.

- Understand that feelings come and go, and it is safe to feel them all.

- Build empathy by recognizing that others (like Milo or Tony) also have feelings.

Secret Learning Objective:

Encourage meta-cognitive awareness by helping children reflect on how emotions affect their behaviour, and foster empathy towards themselves and others.

Plan:

IDEATION:

When I started brainstorming, I first imagined a comic about a child going through everyday situations and experiencing different emotions. As I reflected more, I thought about the children with autism that I work with and how they often find comfort in animals and characters rather than human figures. This led me to shift my idea and create Curious Milo, where a relatable dog models a variety of feelings across simple, sequential panels that combine visuals with short text.

STORYBOARD OR SCRIPT:

The comic follows a 13-panel sequence:

- Milo wagging next to Tony – introduction.

- Tony leaves; Milo thinks, “I’ll miss you…”

- Milo bursts with energy.

- Tony is tired; Milo wants to play.

- Milo feels sad with his ball.

- Milo curled up by the window.

- Dogs turn away at the park.

- Milo with a storm cloud overhead.

- Milo remembers happy moments (memory bubbles).

- Milo howls softly, then cuddles his blanket.

- Tony returns home.

- Tony hugs Milo – “Every feeling is okay.”

- Reflection panel showing that all emotions are natural and safe.

Each slide includes narration, speech bubbles, or thought bubbles to model both external and internal experiences of emotion.

PRINCIPLES APPLIED:

I applied Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML) and multimedia principles:

- Coherence: Each panel focuses on one clear idea or feeling.

- Contiguity: Speech and thought bubbles are placed close to the character.

- Segmenting: The story is broken into short, digestible slides.

- Dual Coding: Text is paired with Milo’s visuals to reinforce meaning.

- Personalization: Text is conversational, using simple, direct language.

- Signaling: Emotion is reinforced with symbols (hearts, storm clouds, sunshine).

Create and Share the Prototype

The final artifact is a 13-panel educational comic titled Curious Milo. It was created using ai-generated, child-friendly visuals in a sketchy style (similar to Charlie and Lola), combined with narration, speech bubbles, and thought bubbles. The sequence models common feelings children may experience and reinforces that every emotion is okay.

While I did use ChatGPT to help generate the base images, I used apps such as Canva and Google Docs to edit the images and style it in the way that represents my personal creativity. Prompts were made to detail and input the script of each comic section, as well as the top newspaper-style framing with the title and peek of Milo in the corner.

PEER FEEDBACK:

I was unable to participate in the peer feedback stage, but I engaged in self-reflection and iterative corrections. This included fixing inconsistencies in text (ensuring correct grammar like “I’ll miss you”), standardizing Milo’s look, and addressing visual continuity. I also that AI-generated images can sometimes produce flaws (extra features, slight colour shifts), and I corrected or regenerated those panels to ensure accuracy.

Reflect and Refine

TEAM REFLECTION:

Since I worked individually, my reflection centers on my own design process. What worked well was the comic’s ability to clearly communicate feelings through Milo’s expressions and thought bubbles. Using a dog character was effective because children often find animals safe and relatable.

If I were to improve the project, I would test it directly with children to see how they respond to Milo and whether the story helps them articulate feelings. I would also add interactive elements, such as prompts asking children to point to the emotion Milo is feeling, or spaces for them to draw their own “feeling bubbles.”

A limitation of this type of multimedia is that while comics are engaging, they are static. They can show feelings clearly, but they don’t allow for dynamic practice the way games or role-plays might. Still, comics are powerful because they combine storytelling with visuals and text in a way that supports children who benefit from structure and predictability.

INDIVIDUAL REFLECTIONS:

As the sole designer, I carried out all stages of the project, from ideation to artifact creation. I learned the importance of consistency when working with AI-generated images, as small details can drift between panels. More importantly, I deepened my understanding of how multimedia learning principles apply to practice: by keeping design simple and structured, I could make an abstract topic like emotions accessible for children.

References:

https://edtechuvic.ca/edci337/2025/09/05/theories-of-multimedia-learning/

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. Images generated using DALL·E. https://chat.openai.com/

Recent Comments